Abstract

Providing adequate and equal access health care is a key goal towards universal health coverage (UHC), but women continue to confront considerable inequities in accessing healthcare, particularly in the emerging regions of Ethiopia. Therefore, we identified the contributing factors to the problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age in emerging regions of Ethiopia. Data from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey were used. A total of 4680 women in reproductive age were included in the final analysis and a multilevel mixed-effect binary logistic regression analysis was done to identify the contributing factors to the problems in accessing health care. In the final model, a p-value of less than 0.05 and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to declare statistically significant factors. We found that 71.0% (95% CI 69.64–72.24%) of women in reproductive age had problems in accessing health care. Unmarried women (AOR = 1.30 95% CI 1.06–1.59), uneducated (AOR = 2.21 95% CI 1.48–3.30) and attended primary school (AOR = 1.58 95% 1.07–2.32), rural resident (AOR = 2.16 95% CI 1.40–2.02), poor (AOR = 2.95 95% CI 2.25–3.86) and middle wealth status (AOR = 1.74 95% CI 1.27–2.40), women who gave two births (AOR = 1.29 95% CI: 1.02–1.64) and not working (AOR = 1.33 95% CI 1.06, − 1.68) and working in agriculture (AOR = 1.88 95% CI 1.35–2.61) were factors that contributed for the problems in accessing health care. A significant proportion of women of reproductive age in emerging regions of Ethiopia face challenges in accessing healthcare, which places the country far from achieving its UHC targets. This issue is particularly prominent among unmarried, poor and middle wealth status, uneducated, non-working, and rural women of reproductive age. The government should develop strategies to improve women’s education, household wealth status, and occupational opportunities which would help to alleviate the barriers hindering healthcare access for women residing in emerging regions of Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The healthcare systems continue to face a challenge in providing accessible, high-quality, comprehensive and integrated care around the world1. Globally, the health community is setting ambitious targets for UHC, and there is an increasing interest in accessing primary health care in low-and middle-income countries2. Accordingly, the UHC includes: financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all3, but half of the world's population lacks adequate access to basic health services4. Maternal health issues continue to be a major source of concern and an unfinished business on the millennium development goal agenda for Africa5. The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in developing countries is 15 times higher than in developed countries6. Reduction of preventable maternal and newborn mortality is vital to the attainment of sustainable development goals (SDGs)7.

Access has been defined as the "degree of fit" between health care clients and the health care system8,9. Whether individuals and groups actually gain access to health services depends on issues such as the availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability, and accommodation of services10. Access to healthcare has been emphasized as the major barrier towards the utilization of maternal health services in low-income countries11,12. Furthermore, women continue to face significant disparities in access to and utilization of healthcare13. The consequences of difficulty in accessing health care among women in reproductive age include unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortion, maternal and child mortality resulting from low family planning uptakes, and home deliveries14,15. However, if all women had access to essential health services, an estimated 74% of maternal deaths could be avoided16.

Ethiopia has a significant contribution for the highest maternal mortality in Africa with 401 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 201717 that can be explained by inaccessibility of health care. In that regard, significant work remains in order to end the millions of preventable child and maternal deaths that occur annually18. In order to reach the rural population in Ethiopia, the primary health care units comprised health posts, which are mainly intended to provide essential health services at the community level by health extension workers19,20. Subsequently, a complete set of care for priority maternal and child health interventions and infectious diseases (tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV) are provided free of charge at all public health facilities. Despite the fact that access to health care has improved, there are still significant geographic differences in health care utilization and outcomes19. Previous studies identified the socio-demographic and economic variables: age, educational status, resident, marital status, and wealth index were the factors contributing to problems in accessing health care21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Currently, the health sector is providing different forms of support to communities and regions left behind, i.e., emerging regions. These regions are characterized by scattered pastoralist and semi-pastoralist societies suffering from extreme poverty30. Pastoralist communities in Ethiopia are generally lagging behind in major health indicators19. Although small numbers of studies have been conducted in different parts of Ethiopia, evidence on problems in accessing health care among reproductive age women remains limited, particularly in emerging regions. As a result, understanding contributors of problems in accessing health care in emerging regions could help health policymakers, implementors, and other key stakeholders in developing strategies to alleviate the identified problems and to promote women's health care access for each segment of the population in the country. More broadly, it allows Ethiopia's government to make substantial progress toward the UHC. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the individual and community level factors that contribute to problems in accessing health care among reproductive age women in emerging regions of Ethiopia.

Methods

Data sources and context

The recent 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data were used in this study, a community-based cross-sectional survey. The EDHS is a five-year national representative household survey conducted by Ethiopia's Central Statistical Agency31. In Ethiopia, during the survey, there are nine regional states (Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambela, South Nation Nationalities and Peoples' Region (SNNPR), Harari and Somali) and two city administrations (Addis Ababa and Dire-Dawa). These nine regions can be divided into emerging regions (Afar, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambela, and Somali) and developed regions (Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, SNNPR, and Harari). The emerging regions are characterized by scattered pastoralist and semi-pastoralist societies suffering from life-threatening poverty30,32.

Population, sampling procedures, and sample size

The EDHS employed two-stage stratified sampling techniques from an existing sample frame, generally the most recent census frame, to select the study participants. In the first stage of selection, the primary sampling units were selected with a probability proportional to their size within each stratum. The primary sampling units are typically census enumeration areas (EAs). The primary sampling units forms the survey cluster. In the second stage, a complete household listing was conducted in each of the selected clusters. Following the listing of the households, a fixed number of households were selected by equal probability systematic sampling in the selected cluster. The overall selection probability for each household in the sample is the probability of selecting the cluster multiplied by the probability of selecting the household within the cluster. In the DHS, all women aged 15–49 years who are regular members of the selected households were eligible for the survey.

In our study, we included all women in reproductive age in the four regions (emerging regions). Finally, a total of 4680 women in reproductive age who reside in emerging regions were identified from the EDHS 2016 and included in this analysis.

Variables and measurements

The dependent variable was problems in accessing health care. The problems in accessing health care among women in reproductive age were measured when a woman has serious problems in accessing health care for herself when she is sick33. In our study, if a woman has at least one of the four serious problems (as listed in Table 1) in accessing health care measurements, we considered as "having problems in accessing health care", otherwise "not having problems"26,34.

This study categorized independent variables into individual and community variables. Variables such as education, occupational status, religion, sex, marital status, family size, and household wealth status, birth in the last 5 years, parity, antenatal care (ANC) follow-up for recent pregnancy, institutional delivery, had at least one birth, contraceptive uses, continuum of care and postnatal care (PNC) check-up were included in this analysis as independent variables.

In order to measure household wealth status, the asset index was used based on data from the entire sample and was calculated separately for rural and urban households. All scores were combined into one asset index and ranked into three categories (poor, middle, and rich). The other categories of independent variables were community level, which included the place of residence, health insurance coverage, region, and media exposure.

Data processing and analysis

Data were extracted, cleaned, recoded, and analyzed using STATA 16. The descriptive statistics were presented in tables, graphs, and narrations. The nature of EDHS data is hierarchical (individuals were nested within communities), which violates the independent assumptions of the standard logistic regression model. Therefore, a multilevel logistic regression analysis model was fitted to identify both the individual and community-level variables that contributed to the problems in accessing health care.

In this study, we fitted four models: (i) null model, a model without explanatory variables; (ii) model I, a model with individual-level factors; (iii) model II, a model with community-level factors; and (iv) model III, a model with both individual and community-level factors simultaneously. Since the models were nested, model comparison and fitness were checked based on the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Likelihood Ratio test35, Median Odds Ratio (MOR,) and deviance (− 2*log likelihood ratio (LLR) values. Model III was chosen as the best-fitted model i.e. model with the lowest deviance. The variation between clusters was assessed by computing ICC36. An ICC greater than 5% is eligible for multilevel analysis; in our analysis, the ICC was 37%.

In the bivariable analysis, variables with a p-value of < 0.2 were considered for the multivariable analysis. Finally, an AOR23 with 95% CI and a p-value of < 0.05 were used to declare significant factors contributing to the problems in accessing health care.

Data quality control

Any data collection procedure, including the EDHS, has the potential to produce outliers or inaccurate data. However, the EDHS implemented various measures to minimize such occurrences and ensure the accuracy of the data. The survey used a standardized methodology and questionnaire, and data collectors received extensive training to minimize errors in data collection. In addition, field supervision and quality control measures were in place to monitor the data collection process and identify any potential issues. The EDHS also conducted data quality checks and data cleaning procedures to identify and correct errors and inconsistencies in the data. In general, the EDHS data considered rigorous quality control processes to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data. Details on the data quality are published in the EDHS 2016 report34. Moreover, we followed the guide to demographic health survey (DHS) statistics33 to ensure data quality and handle missing data.

Ethical considerations

The study used a secondary analysis of publicly available survey data from the DHS program (available at https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/), and the data has no personal identifier. To conduct our study, we registered and requested the dataset from DHS online archive. Then, permission was granted to the authors by the MEASURE DHS program to use this data for this study. Data from the original EDHS were collected under international and national ethical guidelines. The Ethiopian Public Health Institute, the former Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute Review Board, the National Research Ethics Review Committee at the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Institutional Review Board for ICF Macro International and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided ethical approval for the survey.

Results

Description of the study participants

The socio-demographic and economic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 2. Nearly 60% of the women were not going to school. Sixty-four and 72% of women were Muslim religion followers and married, respectively. Majority (62.4%) of the women were in the poor household wealth status; 60.6% of women do not have work; and 51.8% of the household had more than four family members.

Obstetric characteristics and reproductive health services related variables

Table 3 shows the obstetric and reproductive health related variables. Forty five percent of the women did not give birth in the last five years and 12.1% of women use modern and traditional contraceptive methods. Additionally, of the total 2563 women who were assessed for their most recent births, 52.6%, 24.9%, 7.1%, and 3.7% of them were had ANC visits, institutional delivery, PNC check-up till 2 months, and continuum of care (ANC + institutional delivery + PNC), respectively.

Community level factors

Majority (78.0%) of the reproductive women were residing in the rural community and less than half a percent was have health insurance coverage which are presented in Table 4.

Problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age

In our analysis, 71.0% (95% CI 69.64–72.24%) of women of reproductive age were had at least one serious problem in accessing health care in emerging regions of Ethiopia. High problem (57.3%) was observed in getting money for treatment and less (30.6%) problems were found getting permission to go for treatment which are presented in Fig. 1.

Measure of variation using random effects and model fitness

There was a significant variation of problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age across the individual and community level in the emerging regions of Ethiopia. The ICC of problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age in the null model was 0.371 (95% CI 0.312–0.432); meaning 37.1% of the variation in problems in accessing health care among women in reproductive age was due to the differences between clusters (between-cluster variation). The model fitness was checked using the ICC across the four models, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and deviance which are presented in Table 5. Accordingly, model 3; a model with low deviance and AIC was chosen.

Factors associated with problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age

After adjusting for individual and community level factors, women's educational status, marital status, occupational status, wealth index, birth in the last years, residence site was significantly associated with problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age which are presented in Table 6.

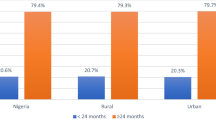

Hence, the odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare among women of reproductive age who are uneducated and these who attended primary school was 2.21 (AOR = 2.21 95% CI 1.48–3.30) and 1.58 (AOR = 1.58 95% CI 1.07–2.32) times higher than those who attended higher education, respectively. Women of reproductive age who gave two births in the last five years were 1.29 times higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare compared to those who did not give birth in the last five years (AOR = 1.29 95% CI 1.02–1.64). The odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare among non-married women of reproductive age were 1.30 times higher than married women (AOR = 1.30 95% CI 1.06–1.59). The odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare among women of reproductive age who were not working and working in agriculture were 1.33 (AOR = 1.33 95% CI 1.06–1.68) and 1.88 (AOR = 1.88 95% CI 1.35–2.61) times higher than those who do have professional work, respectively. Women of reproductive age who are in the poor and middle household wealth status had 2.95 (AOR = 2.95 95% CI 2.25–3.86) and 1.74 (AOR = 1.74 95% CI 1.27–2.40) times higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare than those who are in the rich wealth status, respectively. These women of reproductive age reside in the rural area had 2.16 times higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare than women who reside in the urban area (AOR = 2.16 95% CI 1.40–2.02).

Discussion

We found that 71.0% of women of reproductive age had at least one serious problem in accessing health care in emerging regions of Ethiopia. Of these, difficulty of obtaining money (57.3%) and distance from health facilities (53.3%) were the most frequently mentioned problems in the regions.

Previous studies in Ethiopia supported our findings as reported problems in accessing health care was 70%26 and 72%37. Even though the Ethiopian government has made tremendous efforts to decrease the problems in accessing health care for women, our study revealed that there is still a higher magnitude of problems in accessing health care among women of reproductive age in emerging regions of Ethiopia. Moreover, this finding was higher than studies conducted in South Africa 65%27, Rwanda 64%38, Tanzania 64.5%23, and Ghana 51%39. The higher finings in our study might be explained due to the study settings; emerging regions (Somali, Afar, Gambela, and Benishangul-Gumuz) were economically disadvantaged and characterized by scattered pastoralist and semi-pastoralist societies which make them to prone to problems in accessing health care in contrast to other regions. In addition, sociocultural, topography and economic differences among countries could be the reason for observed differences.

Our study revealed a significant association between lack of education and difficulties in accessing healthcare. Other studies in Ethiopia24,25,26, South Africa21, Ghana39, Sub-Saharan Africa21, and Tanzania23 are also supported our findings. Women of reproductive age who have higher levels of education are more likely to work in higher-paying careers. As a result, they can afford healthcare expenditure regardless of the costs. In addition, they are more aware of their basic human rights and may have better health literacy. Consequently, these educated women of reproductive age are capable to overcoming any type of healthcare challenges than their counterparts, who may also have lower health literacy, which has been identified as a major impediment to health care access29,40. This implies that the government should develop special programs that address the education gaps of women who reside in emerging regions of Ethiopia in order to empower and make them independent.

We found that women who are not currently married had higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing health care compared to married women. Our finding is supported with these of the previous studies in Ethiopia26, Ghana39 and Tanzania23. This implies that married women may advance financial and psychological support from their partners to access healthcare41. In contrast, studies conducted in Malaysia revealed that married respondents had higher barriers compared to those who are unmarried42. The observed difference could be explained due to married women needed permission from their husband or head of household to leave the house or visit health facilities, and their husband may not have given them permission, causing them to have difficulty accessing health care43,44.

In our study, women who lived in the rural areas had higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare than their counterparts. Our finding is supported by previous studies in Ghana39, Sub-Saharan Africa29, South Africa27, Ethiopia26, and Tanzania23. The explanation could be that rural areas have poor health infrastructure i.e. geographical inaccessibility of health facilities, less privileged and the influences of socio-cultural practices that need women to seek permission from their spouses before visiting healthcare or women's decisions for seeking healthcare services is under their husband/partners control26. Moreover, male involvement and support for women health care access are limited26. This implies that the government should expand infrastructure services. In addition, efforts should be exerted to encourage male involvement and support for improving health care access for reproductive age women.

In our study, we found that women who are in the poor and middle household wealth status had higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing health care. This finding might be explained by women in the poorest households facing a challenge to cover their basic needs, such as food, and therefore less likely to afford healthcare cost39,45,46 and supported by other previous studies in Ethiopia, Tanzania, Egypt, Ghana, and Afghanistan23,26,28,47,48. The finding indicates that there is a need to develop strategies and initiatives that safeguard pastoralist inhabitants against drought, flood and social unrest which help to improve their socio-economic status and diminish the barriers that hinder health care access for women of reproductive age.

We found that women who were not working and working in agriculture had higher odds of experiencing problems in accessing health care than those who did have professional work. The finding is supported by other studies in Ghana39, Malaysia49, Tanzania23 and United Kingdom50. This could be because women who have good occupations have enough income and independence to afford their health-care costs, allowing them to overcome the health-care access barrier29. In contrast, another study conducted in Ethiopia26 showed that no significant association between unemployment and problems in accessing healthcare. This could be due to being employed is not enough to have full access to healthcare as there are other problems preventing women from accessing healthcare, such as poor infrastructure, gender inequality, and lack of knowledge regarding health services23. The finding implies that it is better to create job opportunities for women who reside in emerging regions to overcome one of the problems in accessing health care; financial hardship.

In our study, to the odds of experiencing problems in accessing healthcare among women who gave two births in the last five years was higher compared to those who had not given birth. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa countries29. This could be because women have responsibilities for taking care of their children and the household, and due to this, they are unable to leave their homes and become reluctant to seek health care51. This implies that the government should establish a strong public health system that is responsible for ensuring that all women who have children have access to primary and preventive health care services.

Strength and limitations of the study

This study used a nationally representative data with a large sample size as a strength. The study also employed advanced statistical models, which considered the hierarchical nature of the DHS data to get reliable estimates. Moreover, since it is based on the national survey data the study has the potential to give insight for the policymaker and program planners to design appropriate interventions for Pastoralist communities in Ethiopia those lagging in major health indicators.

Despite these strengths, the study finding is interpreted in light of limitations. Supply side predicators of the outcome variables are not included owing to the use of secondary data. Moreover, women might have experienced recall bias, particularly regarding the problems they encountered in the previous five years.

Conclusions

This study finding revealed that significant proportion of women of reproductive age in emerging region of Ethiopia had experienced problems in accessing health care. This was particularly more pronounced among unmarried women, those in poor and middle quintiles, uneducated and women who attend primary school, women who were not working and working in agriculture, rural residents, and women who gave two births. Even though the government has attempted to incorporate pastoral development in its national development plan (2005–2009), our study finding showed that still great efforts needed to address the identified problems in accessing health care in emerging regions of Ethiopia. Therefore, the government should develop strategies that improve women education, household wealth status, and women occupational status to diminish the barriers that hinder health care access for women living in emerging regions of Ethiopia.

Data availability

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health surveys. The database was available at official website of DHS is at https://dhsprogram.com/.

References

Schneider, H., Langlois, É. V., & McKenzie, A. Measures to strengthen primary health-care systems in low-and middle-income countries (2020).

Organization WH. Primary health care systems ( primasys): case study from Ethiopia (World Health Organization, 2017).

WHO. The 2030 sustainable development goal for health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/sustainable-development-goals#tab=tab_1.

Organization WH. World health statistics 2018: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals (World Health Organization, 2018).

Kumar, S., Kumar, N. & Vivekadhish, S. Millennium development goals (MDGS) to sustainable development goals (SDGS): Addressing unfinished agenda and strengthening sustainable development and partnership. Indian J. Community Med. 41(1), 1 (2016).

Africa UNECf. Report on progress in achieving the Millennium Development Goals in Africa. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Addis Ababa (2013).

Pablos-Mendez, A., Valdivieso, V. & Flynn-Saldaña, K. Ending preventable child and maternal deaths in Latin American and Caribbean countries (LAC). Perinatología y reproducción humana. 27(3), 145–152 (2013).

Oliver, A. & Mossialos, E. Equity of access to health care: Outlining the foundations for action. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 58(8), 655–658 (2004).

Penchansky, R. & Thomas, J. W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care. 1, 127–140 (1981).

Gulliford, M. et al. What does’ access to health care’mean?. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 7(3), 186–188 (2002).

Odetola, T. D. Health care utilization among rural women of child-bearing age: A Nigerian experience. Pan Afr. Med. J. 20, 1 (2015).

Victora, C. G. et al. How changes in coverage affect equity in maternal and child health interventions in 35 Countdown to 2015 countries: An analysis of national surveys. The Lancet. 380(9848), 1149–1156 (2012).

Ganle, J. K., Parker, M., Fitzpatrick, R. & Otupiri, E. Inequities in accessibility to and utilisation of maternal health services in Ghana after user-fee exemption: A descriptive study. Int. J. Equity Health. 13(1), 1–19 (2014).

Erasmus, M. O. The barriers to access for maternal health care amongst pregnant adolescents in the Mitchells plain sub-district (2017).

Nyakango, S. B. & Booth, A. Women’s perceived barriers to giving birth in health facilities in rural Kenya: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Midwifery 67, 1–11 (2018).

Wagstaff, A. The Millennium Development Goals for health: Rising to the challenges (World Bank Publications, 2004).

Organization WH. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division (2019).

Ruducha, J. et al. How Ethiopia achieved millennium development goal 4 through multisectoral interventions: A countdown to 2015 case study. Lancet Glob. Health. 5(11), e1142–e1151 (2017).

Admasu, K., Balcha, T. & Ghebreyesus, T. A. Pro-poor pathway towards universal health coverage: lessons from Ethiopia. J. Glob. Health. 6(1), 1 (2016).

Alebachew, A., Hatt, L. & Kukla, M. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Ethiopia. PLOS Med. 11(9), e1001696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001696 (2014).

Tsawe, M. & Susuman, A. S. Determinants of access to and use of maternal health care services in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: A quantitative and qualitative investigation. BMC Res Notes. 7(1), 1–10 (2014).

Kyei-Nimakoh, M., Carolan-Olah, M. & McCann, T. V. Access barriers to obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa—a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 6(1), 1–16 (2017).

Bintabara, D., Nakamura, K. & Seino, K. Improving access to healthcare for women in Tanzania by addressing socioeconomic determinants and health insurance: A population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 8(9), e023013 (2018).

King, R., Jackson, R., Dietsch, E. & Hailemariam, A. Barriers and facilitators to accessing skilled birth attendants in Afar region Ethiopia. Midwifery 31(5), 540–546 (2015).

Okwaraji, Y. B., Webb, E. L. & Edmond, K. M. Barriers in physical access to maternal health services in rural Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15(1), 1–8 (2015).

Tamirat, K. S., Tessema, Z. T. & Kebede, F. B. Factors associated with the perceived barriers of health care access among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: A secondary data analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20(1), 1–8 (2020).

Silal, S. P., Penn-Kekana, L., Harris, B., Birch, S. & McIntyre, D. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12(1), 1–12 (2012).

Chiang, C., Labeeb, S. A., Higuchi, M., Mohamed, A. G. & Aoyama, A. Barriers to the use of basic health services among women in rural southern Egypt (Upper Egypt). Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 75(3–4), 225 (2013).

Seidu, A.-A. Mixed effects analysis of factors associated with barriers to accessing healthcare among women in sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE 15(11), e0241409 (2020).

Debie, A. & Lakew, A. M. Factors associated with the access and continuum of vaccination services among children aged 12–23 months in the emerging regions of Ethiopia: Evidence from the 2016 Ethiopian demography and health survey. Ital. J. Pediatr. 46(1), 1–11 (2020).

Csa I. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA (2016).

Gebre-Egziabhere, T. Emerging regions in Ethiopia: Are they catching up with the rest of Ethiopia?. East. Afr. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 34(1), 1–36 (2018).

Croft, T. N., Aileen, M. J. Marshall, Allen, C. K., et al. Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF (2018).

Csa I. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. 1 (2016).

Nes, R. B. et al. Adaptation to the birth of a child with a congenital anomaly: A prospective longitudinal study of maternal well-being and psychological distress. Dev. Psychol. 50(6), 1827 (2014).

Shimelis, N. D. et al. Researching accessible and affordable treatment for common dermatological problems in developing countries: An Ethiopian experience. Int. J. Dermatol. 51(7), 790–795 (2012).

Zegeye, B. et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing health care services among married women in Ethiopia: A multi-level analysis of the Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Int. J. Transl. Med. Res. Public Health. 5(2), 183–196 (2021).

Nisingizwe, M. P., Tuyisenge, G., Hategeka, C. & Karim, M. E. Are perceived barriers to accessing health care associated with inadequate antenatal care visits among women of reproductive age in Rwanda?. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20(1), 1–10 (2020).

Seidu, A.-A. et al. Barriers to accessing healthcare among women in Ghana: A multilevel modelling. BMC Public Health 20(1), 1–12 (2020).

Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J. & Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 155(2), 97–107 (2011).

Ani, F. et al. Demographic factors related to male involvement in reproductive health care services in Nigeria. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 21(1), 57–67 (2016).

Abd Wahab, S. N., Satar, N. M., & Tumin, M. Socio-demographic factors and structural barrier in accessing public clinics among the urban poor in Malaysia. e-BANGI. 17(3), 71–81 (2020).

Shaikh, B. T. & Hatcher, J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J. Public Health 27(1), 49–54 (2005).

Mistry, R., Galal, O. & Lu, M. Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: A contextual analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 69(6), 926–933 (2009).

Yaya, S., Bishwajit, G. & Shah, V. Wealth, education and urban–rural inequality and maternal healthcare service usage in Malawi. BMJ Glob. Health 1(2), e000085 (2016).

Mwangome, F. K., Holding, P. A., Songola, K. M. & Bomu, G. K. Barriers to hospital delivery in a rural setting in Coast Province, Kenya: Community attitude and behaviours. Rural Rem. Health. 12(2), 7–14 (2012).

Badu, E., Gyamfi, N., Opoku, M. P., Mprah, W. K. & Edusei, A. K. Enablers and barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among visually impaired women in the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo regions of Ghana. Reprod. Health Matters 26(54), 51–60 (2018).

Steinhardt, L. C. et al. The effect of wealth status on care seeking and health expenditures in Afghanistan. Health Policy Plan. 24(1), 1–17 (2009).

Makmor, T., Khaled, T. & NurulHuda, M. Demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with access to public clinics. J. Health Transl. Med. 21(1), 1 (2018).

Field, K. S. & Briggs, D. J. Socio-economic and locational determinants of accessibility and utilization of primary health-care. Health Soc. Care Community. 9(5), 294–308 (2001).

Council NR, editor Benefits and Systems of Care for Maternal and Child Health Under Health Care Reform Workshop Highlights. Paying Attention to Children in a Changing Health Care System: Summaries of Workshops; 1996: National Academies Press (US).

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to the major DHS program which permitted us to use the DHS survey data sets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.F., and T.G.H. conceived the idea for this study; S.M.F. is involved in the data extraction, analysis, interpretation of the finding and writing the original draft. T.G.H. assisted in the analysis of the study and editing the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fetene, S.M., Haile, T.G. Three fourths of women of reproductive age in emerging regions of Ethiopia are facing problems in accessing health care. Sci Rep 13, 10656 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36223-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36223-z

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.