Abstract

We analyze whether the introduction of the general minimum wage in Germany in 2015 had an effect on workers’ self-rated health. To this end, we use survey data linked to administrative employment records and apply difference-in-differences regressions combined with propensity score matching. This approach enables us to control for a vast set of potential confounding variables. We find a health improving effect among the individuals who were most likely to be affected by the reform. Our results indicate that workers’ improved satisfaction with pay, their reduced working hours, and a reduction in time pressure at work may drive this result.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2015, the first uniformly binding federal minimum wage of €8.5 was introduced into the German labor market. According to Bellmann et al. (2015), approximately 12 % of all establishments employed at least one worker with a wage below the minimum wage in the year prior to the reform. Prior to 2015, minimum wages had been implemented only in certain industries.

Both policymakers and researchers have been predominately interested in the effects of minimum wages on labor market outcomes such as employment or the wage distribution.Footnote 1 However, research on the effects of minimum wages on nonlabor market outcomes is relatively sparse. By law, one particular goal of the minimum wage evaluation is the protection of workers (see§9 MiLoG), especially the protection of workers’ well-being. Accordingly, in their first evaluation report [see Mindestlohnkommission (2016)] the German Minimum Wage Commission declared the analysis of the effects of the minimum wage on public health an important avenue for future research.

In this paper, we aim to shed light on the effects of the introduction of the German minimum wage on workers-self-rated health. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to study the introduction of the German minimum wage as a natural experiment in the health context.Footnote 2 To this end, we use survey data from the German Institute for Employment Research (IAB) combined with high-quality administrative records from the Federal Employment Agency ("PASS-ADIAB")Footnote 3 and apply regression-adjusted difference-in-differences models with matching to identify the health effects of the minimum wage reform. Treated and control individuals are categorized according to their hourly wages in the year prior to the reform: individuals with hourly wages below €8.5 are assigned to the treated group, while individuals earning hourly wages of at least €8.5 are assigned to the control group. Our estimates indicate that the introduction of the minimum wage is related to significant improvements in self-rated health. We find that individuals who were most likely affected by the introduction of the minimum wage have on average a 4–7 percentage-point higher probability of assessing their own health as good or very good. A variety of robustness checks support this result.

To put this positive health effect into perspective, we analyze potential pathways and compare our results to results from the previous literature. In this context, Paul Leigh et al. (2019) identify three main pathways—affordability, worker and firm decision-making, and psychosocial effects. These channels are not mutually exclusive and could interact and generate compound effects. Hence, it is ultimately an empirical question whether and how the minimum wage affects workers’ health. To test the relevance of these pathways in the context of the introduction of the minimum wage, we utilize proxies from our survey data.

Our results point to a positive income effect (affordability). The monthly wage of workers in the treatment group increased by approximately 5–7%. We find a significant simultaneous reduction in working hours for individuals affected by the minimum wage reform. The literature has shown that individuals may use their increased income to consume more healthcare, for example, through better nutrition or medicine (Horn et al. (2017) among others). Moreover, if working hours are reduced in response to higher wages, workers may use their additional time to improve their health by investing in nonmarket goods such as exercise or rest [see Lenhart (2017b)]. On the other hand, an increase in wages raises the opportunity costs of time, which makes investing in nonmarket goods more expensive (Horn et al. 2017) (decision making).

Interestingly, we do not find that affected individuals spend their additional time exercising more. However, we find evidence for the relevance of the psychosocial and stress-related pathways (Backé et al. 2012). Affected individuals report that they feel less time pressure at work and are more satisfied with their pay and economic status.

1.1 Related literature

Our paper is related to several recent studies that examine the effects of minimum wages on different health outcomes. Most of the studies similar to our work have analyzed the health effects of the 1999 introduction of a national minimum wage in the UK (Reeves et al. 2017; Kronenberg et al. 2017; Lenhart 2017a). Reeves et al. (2017) find significant improvements in mental health after the minimum wage introduction, which is potentially driven by a reduction in financial strain. The estimates from Kronenberg et al. (2017) do not support these results, as they do not provide evidence of mental health improvements among affected workers while using the same data. Lenhart (2017a) finds significant improvements in self-rated health and other measures of health.

Furthermore, Andreyeva and Ukert (2018) find minimum wage increases to be positively associated with health care access and self-rated health, which is the main outcome of interest in our study. Du and Leigh (2017) provide evidence for a negative association between the minimum wage and absence from work due to illness. This is possibly driven by health changes, as they also detect significant improvements in self-rated health after minimum wage increases. Horn et al. (2017) analyze whether an increased minimum wage improves the self-rated health of workers. Their results do not suggest that this is the case. In contrast, their estimates even suggest a deterioration of self-rated health for unemployed male workers. Averett et al. (2017) obtain heterogeneous self-rated health effects of minimum wage increases among teenagers of different ethnicities. For those actually experiencing an increase in earnings, only white women rated their health as better, while white men and Hispanic women did not, on average, significantly alter their self-rated health.

In addition, some of the literature analyzes the relationship between the minimum wage and risky health behaviors. Using US data, Adams et al. (2012) and Sabia et al. (2014) find that a higher minimum wage increases alcohol-related traffic fatalities among teenagers. Andreyeva and Ukert (2018) find that minimum wage increases lower the consumption of fruits and vegetables and raise the probability of being obese. This finding is, however, not supported by Clark et al. (2020), who show that increases in the minimum wage might have modest but positive effects on fruit and vegetable consumption.

Most of the authors apply difference-in-differences models to identify the effects of interest. However, the definitions of the treated and control groups usually differ across studies. Studies analyzing health-related effects for the US mostly exploit variation in the minimum wage across or within states. Usually, the treated group consists of individuals who reside in states with changes in minimum wage regulations, while control group members reside in states without changes in minimum wage regulations. In contrast, our study and studies analyzing the UK minimum wage reform use individual hourly wages to define the treated and control groups. Individuals in the treated group earn hourly wages below the minimum wage prior to the reform, whereas control group members earn hourly wages at least as high as the minimum wage prior to the reform. Our paper contributes to this literature by examining the effect of the German minimum wage reform on the self-rated health of affected individuals. Due to the mixed findings in the previous literature and the limited external validity of studies in non-German settings caused by institutional differences between the US, UK and German labor and healthcare markets, the analysis of the health effects generated by the German reform is a relevant extension of existing studies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the estimation procedure and describes the outcome variable and the covariates. Section 3 provides information about the data used and the estimation sample. Section 4 presents descriptive statistics and results of the matching approach. Section 5 presents the estimation results. Section 6 and 7 discuss potential limitations and present several robustness tests. Section 8 analyzes potential pathways between the minimum wage reform and health. Section 9 concludes.

2 Estimation procedure

2.1 Treatment assignment and regression specification

To identify the effect of the German minimum wage reform on self-rated health, we rely on matching techniques and regression-adjusted difference-in-differences models, as suggested by Heckman et al. (1997). Self-rated health is the most extensively used measure of health in a variety of research fields, such as the medical, social, and behavioral sciences (Garbarski 2016). It is widely accepted as a valid and efficient measure of physical and mental health (see Eriksson et al. (2001); Bacak and Olafsdottir (2017) among others).Footnote 4

The definition of the treatment and control groups is based on an individual’s hourly wage prior to the reform. This is a common approach in the literature that evaluates minimum wage reforms [see Bossler and Broszeit (2017), Kronenberg et al. (2017), Arulampalam et al. (2004), Stewart (2004)]. among others) Specifically, treated individuals earn an hourly wage below €8.5, while individuals in the control group earn an hourly wage of at least €8.5 in their main job at the time of the interview in the year prior to the introduction of the minimum wage. The underlying idea behind this definition is that individuals in the treatment group should be affected by the minimum wage reform, while individuals in the control group should not be affected. The following regression model shows our main specification:

\(y_{i,t}\) is a measure of the self-rated health of individual i in year t. \(d(treated)_i\) is an indicator variable equal to one if an individual is treated in the sense of being affected by the minimum wage reform and zero otherwise. \(d(post)_t\) is an indicator equal to one if t is equal to 2015 or 2016, the post reform years in our sample. \(X_{i,t}\) is a vector of demographic, socioeconomic, and individual-level characteristics that we specify in greater detail below. \(\tau _t\) is a time trend, \(\gamma \) is an individual-specific fixed effect capturing all time-constant differences between affected and unaffected individuals.Footnote 5 The treatment effect \(\delta \) estimates the difference in self-reported health for the group of affected individuals. \(\epsilon _{i,t}\) is an idiosyncratic error clustered at the individual level.

We do not restrict the analysis to individuals who actually receive or do not receive the minimum wage. Hence, we identify the intention-to-treat (ITT) effect, which may differ from the average treatment effect on the treated. Previous literature shows that due to potential measurement error in hourly wages or due to a lack of compliance by employers, there may be individuals who do not receive the minimum wage even though they are in the treatment group [see, Lenhart (2017a) among others]. Both noncompliance and measurement error might attenuate the effect towards zero. Hence, we think that the ITT effect represents a conservative measure of the treatment effect.Footnote 6

There seems to be no clear-cut consensus with respect to which upper hourly wage threshold should be chosen to define the control group. Some authors, such as Stewart (2004) or Reeves et al. (2017), use a very low upper hourly wage threshold of 110% of the minimum wage. Others use higher thresholds: Kronenberg et al. (2017) use 140%, Pusch and Rehm (2017) and Gülal and Ayaita (2018) use approximately 150%, and Lenhart (2017a) use approximately 170%, whereas Bossler and Broszeit (2017) use no upper threshold at all. The main purpose of a narrowly defined hourly wage band for the control group is to ensure the comparability of the treated and control groups, as comparability seems plausible for individuals whose hourly wages are very close. We use an upper hourly wage threshold of €20 (235% of the minimum wage) in our benchmark specification but run a series of additional regressions over a grid of upper thresholds to check the sensitivity of our results.

2.2 Matching procedure

The crucial assumption for the identification of the difference-in-differences method is that individuals in the treatment and control groups would have had the same parallel trends with respect to the outcome variable had the intervention not taken place. This assumption can never be tested since the counterfactual is never observed. Below, we graphically check whether the common trends assumption is plausible.

To potentially reduce the risk of violating the identifying assumptions, we perform regression-adjusted difference-in-differences models with matching. The matching is done using kernel matching, which implies that individuals in the control group are reweighted according to their propensity score. The matching is based on demographics, socioeconomic status, labor market-related outcomes, and past self-rated health. This method relies on the assumption that conditional on the observables used to match individuals, the share of individuals who rate their health as good or very good would have developed similarly if the minimum wage reform had not taken place. We again check graphically whether this conditional independence assumption is plausible. Furthermore, we discuss the limitations that may come with our approach.

For the matching approach, we follow Marcus (2014) and take the following steps. First, we run a probit model to estimate the propensity scores, that is, the probability of being affected by the minimum wage reform conditional on the observable control variables, which, as mentioned above, include demographic, socioeconomic, and labor market-related pretreatment covariates in one specification and pretreatment self-rated health outcomes in another specification. Individuals from the treated group whose propensity score was above/below the maximal/minimal propensity score in the control group, that is, those outside the region of common support, were excluded. Next, we follow Heckman et al. (1997) and Marcus (2014) and perform kernel matching to obtain the weights (using an Epanechnikov kernel with bandwidth of 0.09).Footnote 7 We tried other matching algorithms, e.g., nearest-neighbor matching with and without calipers and varying the number of neighbors. However, kernel matching performed best in terms of the overall standardized bias. Subsequently, we run weighted regressions using the weights obtained from matching.Footnote 8

3 Data

3.1 Data sources

Our primary data source is survey data from the German panel study ’Labour Market and Social Security’ (PASS). The PASS is a longitudinal survey of households in Germany conducted annually by the Institute for Employment Research (Trappmann et al. 2010). The PASS was originally established to study the effects of the largest labor market reforms in Germany—the ’Hartz reforms’—and low-income households are oversampled.Footnote 9 Hence, the PASS provides comparably high numbers of individuals who are most likely to be affected by the minimum wage reform.

The survey data can be linked to individual administrative data from the social security system [PASS-ADIAB, see Antoni et al. (2014)]. The administrative data complement the survey information. For each employment spell that is subject to social security, the data provide information such as the exact start and end dates as well as worker and employer characteristics.Footnote 10

3.2 Sample construction

We use waves 5–10 (years 2011–2016) of the PASS-ADIAB.Footnote 11 The pre-reform period is from 2011-2014, and the post-reform period is from 2015-2016. We exclude workers who are legally exempted from the minimum wage either temporarily or permanently. Those permanently excluded are long-term unemployed individuals, apprentices, interns, and individuals aged below 18 years who have not completed vocational training.Footnote 12 Temporary exemptions are for employees in branches with already existing industry-specific minimum wages or other special legal regulations.Footnote 13 The linkage with administrative establishment data helps us to properly identify these exemptions. Additionally, we exclude individuals with missing or inconsistent information on working hours, wages, or employment status. After all data preparations, the sample comprises 2,484 individuals. These individuals are employed either full- or part-time with social security contributions in 2014 and are potentially affected by the minimum wage reform. There are 620 treated and 1,864 untreated individuals (for whom we had a full set of observable variables). Matching without past self-rated health does not reduce the sample size, that is all observation are in the common support. However, matching including past self-rated health reduces it to 1,563 untreated and 482 treated individuals.Footnote 14 We do not impose any further restrictions on employment status in the year of the reform, as we want to capture the total health effect of the reform—this includes potential employment effects that could influence self-rated health.Footnote 15 In a robustness check, we additionally use a sample in which only individuals who are employed both before and after the reform are taken into account. This restriction does not alter our findings (see Table C.3 of “Online Appendix” C).

4 Empirical analysis

The main outcome variable is workers’ self-rated health. In particular, we use the answer to the question ‘How would you describe your general health status in the last four weeks?’, where the five possible answer categories range from very good to bad. Table 1 shows that the distribution of workers’ self-rated health in our sample years is left-skewed with few observations at the tails (bad and very good).

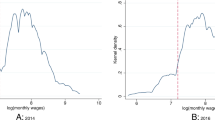

To cope with these small observation numbers, we propose two different strategies. First, we create a binary outcome variable that takes on the value one if the individual claims to be in very good or good health, while the value zero represents satisfactory, poor or bad self-rated health. The advantage of this specification is that it allows us to account for unobserved worker heterogeneity by including individual fixed effects. One caveat with bunching categories into a binary outcome variable is, however, that we may lose important information. To establish the robustness of the estimates using the binary outcome variable, we additionally estimate cross-sectional and logit regressions. To exploit additional qualitative levels of the outcome variable, we additionally estimate ordered logit models. For these regressions, we create an ordinal variable with three values by merging bad with poor and good with very good. Figure 1 shows the pre- and post-reform distribution of self-rated health.

Another crucial variable is workers’ hourly wages because they directly determine treatment status. To calculate hourly wages, we divide the self-reported monthly gross wage by the self-reported average monthly working hours (including overtime).Footnote 16 We use the workers’ actual working hours, rather than their contractual hours, because potential overtime hours are subject to the minimum wage regulation as well.

Linking the survey data with the administrative records also allows us to control for labor market-related characteristics, including the total number of days in regular employment, the number of days in the current job, the total days with social benefit receipt, part- or full-time status, and the firm size of the individual’s current employer. In addition, we use a broad set of covariates, which can be categorized into demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics. Demographic covariates include age, gender, migration background, and region of residenceFootnote 17.

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and Matching Results

Columns one, two, and three of Table 2 show the mean values of the main variables of interest for the treated group and the control group (both before and after propensity score matching), respectively (see Table A.1 of “Online Appendix” A) for more detailed statistics for the control variables in the year prior to the reform). Columns four and five of Table 2 display the standardized differences between the treated and control groups before and after propensity score matching, respectively.Footnote 18

The average standardized bias before matching (25.98) indicates rather large covariate differences between the treated and control groups, which are reduced substantially by the matching procedure (mean standardized bias after matching of 1.77). Before matching, significant differences between the treated and control groups were found, especially among the labor market-related variables. Individuals in the treated group had on average spent fewer days in employment and more days receiving social benefits, worked in companies with fewer employees and worked on a part-time basis more frequently. The socioeconomic variables were also significantly different before matching. Individuals in the control group were more likely to be married. Furthermore, individuals in the control group had on average a higher level of education. Among the demographic variables, it is notable that the proportion of people living in Eastern Germany is significantly higher in the treated group than in the control group. The proportion of women in the treated group was higher than that in the control group.

Share of individuals with good or very good self-rated health. Notes The figure illustrates how the share of individuals who rate their health as good or very good developed over time The left panel illustrates this development for the sample before matching The right panel shows this development for the weighted sample after propensity score matching including past self-rated health outcomes and the other covariates. Source: PASS-ADIAB

Figure 2 displays the development of the share of individuals in good or very good health for the treated (crosses) and control (diamonds) groups for the years 2011 to 2016 before and after propensity score matching separately. The identifying assumption for our estimation approach is that the share of individuals who rate their health as good or very good would have developed similarly if the minimum wage reform had not taken place. For this assumption to hold, the lines should be parallel before the intervention.

Before matching, the pre-reform trends are similar but not parallel. Differences in the trends seem to be highest between 2013 and 2014, since for the treatment group, the share is rather constant, whereas it increases for the control group. After matching, however, the parallel trend assumption does not seem to be violated, as the lines are fairly parallel in the right panel. Both panels reveal a substantial increase in self-rated health for the treated group after the reform in 2015. In 2016, one year after the introduction of the minimum wage, the share was still higher among individuals in the treatment group than among those in the control group. In the next section, we present a more formal test of this assumption, in which we allow for leads and lags of the treatment.

Testing parallel trends. Notes the figures show the estimated interaction-term coefficients from a regression of self-rated health on year dummies, the treatment indicator, and their interactions The reference year is 2014, the year prior to the minimum wage introduction 95% confidence intervals; standard errors are clustered at the individual level. Source: PASS-ADIAB

5 The effect of the minimum wage on self-rated health

Before we turn to our main regression specification, we probe the robustness of the difference-in-differences identification. To this end, we follow Autor (2003) and regress self-rated health on year dummies and the treatment indicator as well as their interactions (leaving out 2014, the year prior to the reform). If the trends in the health outcome between the treatment and control groups are the same, then we should not observe significant coefficients on the lead (pretreatment) interactions. Figure 3 shows the estimated coefficients without matching (left panel) and with matching (right panel). As expected from the previous graphs, we do not find any significant effects in the pretreatment years, indicating that the difference-in-differences strategy is feasible.

Next, we show the regression results for our main specifications as laid out in equation 1. Table 3 shows the estimated treatment effects. The first two columns contain the estimation results for the specifications without matching. Columns three and four contain the estimation results for the models with matching on observable worker characteristics. Columns five and six report the estimation results with matching, including on workers’ past health.

In all the regressions presented in Table 3, we find a positive and statistically significant treatment effect. The magnitude of the effect implies that the introduction of the minimum wage has on average increased the treated individuals’ probability of assessing their health as good or very good by 4 to 7 percentage points. This effect is slightly higher in the models with matching.

In “Online Appendix” C.1, we show results of additional model specifications, that is cross-sectional OLS, cross-sectional logit, and random effects ordered logit models. In all of these regressions, we again find positive, statistically significant treatment effects.

6 Discussion

In the following, we discuss possible limitations of our approach. We consider measurement error, anticipation effects, and comparability issues that might threaten the validity of our results.

6.1 Measurement error in the hourly wage measure

As mentioned above, the reported actual working hours may differ from true working hours, and thus, the calculated hourly wage may differ from the true hourly wage. If individuals who already receive an hourly wage above the minimum wage threshold are falsely assigned to the treated group, we would expect the true effect of the minimum wage reform to be underestimated.Footnote 19

The probability of falsely assigning individuals to the treated or control group should be higher the closer the calculated hourly wage is to the minimum wage threshold of €8.5 [see, Bonin et al. (2018), Pusch and Rehm (2017) among others]. To assess the robustness of our previous results, we exclude individuals whose calculated hourly wage is in the vicinity of the minimum wage. If systematic misclassification is an issue, we would expect an increase in the estimated coefficients from these specifications compared to the estimates that include individuals close to the threshold.

Table 4 shows that systematic misclassification in the vicinity of the minimum wage threshold does not seem to alter our previous results. In specification A, we exclude all individuals whose calculated hourly wage is between €8.25 and €8.75. In specification B, we exclude all individuals whose hourly wage is either 5% above or below the minimum wage threshold. The results for both specifications are very similar to the regression results from our benchmark specification (Table 3). The estimated coefficients range between 0.04 and 0.08. From these results, we conclude that measurement error does not seem to substantially bias the estimates of the treatment effect.

6.2 Anticipation effects

The minimum wage became effective on 1 January 2015. The final parliamentary decision was made in July 2014. However, the introduction date and the level of the minimum wage were publicly announced in April 2014. Similarly, in June 2016, the Minimum Wage Commission announced an increase in the minimum wage to 8.84 Euro from January 2017 onward. These announcements make it possible that some establishments could have increased their wages prior to 2015/2017, which would then imply that there could be selection out of treatment. Indeed, Bossler and Gerner (2019) find evidence for anticipation/announcement effects. To test the internal validity of our benchmark specification, we exclude observations from after April 2014 from our 2014 observations and from after June 2016 from our 2016 observations. We then rerun our set of regressions. Table 5 shows coefficients of similar sizes (0.04–0.07) to those of our benchmark specification. We conclude that anticipation/announcement effects are unlikely to have influenced our results.

6.3 Comparability of the control group

A necessary assumption is that the difference in hourly wages before the policy intervention is unrelated to the error term conditional on the control variables. This seems like a reasonable assumption to make when the difference in wages is not large. To test the robustness of our previous estimation results, we vary the upper hourly wage threshold from 12 to 50 Euros. Figure 4 displays the estimated treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals from each regression. The estimated coefficients are close to 0.05, indicating a rather robust treatment effect. All specifications return coefficients that are significant at least at the 10% level.Footnote 20

Upper hourly wage thresholds for the control group. Notes The figure displays the estimated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals of the ITT effect for various upper hourly wage thresholds for the control group, which are displayed on the x-axis Note that the number of individuals in the control group increases in the upper hourly wage threshold The bar with an upper hourly wage of €20 represents the main specification. Source: PASS-ADIAB

6.4 Location

In our benchmark specification, we use an indicator for people who live in Eastern Germany, where the bite of the minimum wage policy has been found to be stronger (Bossler et al. 2020; Ahlfeldt et al. 2018). However, even within Eastern Germany, it might be the case that individuals from the treatment and control groups are located in two very different regions and are hence affected very differently. To test whether our previous results depend on the individuals’ locations, we draw upon our administrative data and utilize information on the exact federal state in which the individuals are located. We include a dummy variable indicating the federal state of the place of work and rerun our matching procedure.Footnote 21 Table 6 shows that our previous conclusion is unaffected by using more detailed information on individuals’ locations.

7 Robustness

7.1 Placebo reform

Following Lenhart (2017a) and Gülal and Ayaita (2018), we perform placebo tests. Accordingly, we pretend that the reform took place in 2014, which is one year prior to the actual minimum wage reform. Table 7 shows that, keeping all other factors from the main specification constant, the placebo reform does not induce significant effects on self-rated health. We interpret this as support for our main result.

7.2 Additional robustness checks

We perform a series of additional robustness checks that are presented in “Online Appendix” C: (i) To rule out the possibility that our results are driven by spillover effects, we estimate our model over a grid of lower hourly wage thresholds used to define the control group. (ii) We perform additional placebo tests and alter the composition of the treatment and control group to the extent that the reform should not affect either of them as hourly wages in both groups are considerably above the minimum wage threshold. (iii) We vary the upper hourly wage threshold and combine it with a placebo reform. Hence, we estimate a placebo reform that took place in 2014 and estimate the effects of this placebo reform over a grid of upper hourly wage thresholds. iv) We narrow down the treatment group and vary their lower hourly wage threshold.

These additional checks support our main result: a significantly positive minimum wage effect on self-rated health.

8 Potential pathways between minimum wages and health

Paul Leigh et al. (2019) review the literature on the effects of minimum wages on public health. They identify three main pathways: affordability, psychosocial effects, and worker and firm decision making.

The affordability mechanism is related to the model proposed by Grossman (1972). In this framework, higher wages can be interpreted as a positive income shock that may increase the consumption of healthcare (e.g., better nutrition, medicine). However, higher wages might also be related to increased purchases of cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs (Chaloupka and Warner 2000).Footnote 22 Hence, the affordability effect on health is a priori ambiguous.

Physiological and psychological health are often associated with worker job satisfaction. Faragher et al. (2005) show that dissatisfaction at the workplace is indeed an important hazard for worker well-being. Another determinant might be that higher income is often related to a higher social status. In this context, the literature has shown that income inequality is related to worse health [see Pickett and Wilkinson (2015) among others]. In addition, Kaufman et al. (2020) show that higher minimum wages in the USA are related to lower suicide rates, which might be driven by improved mental health through perceived social status when unemployed join the labor force.

Finally, the last pathway involves worker and firm decision making. Grossman (1972) emphasizes the investment motive of workers, which postulates that higher income results in increased opportunity costs of poor health. Poor health today may result in smaller income streams in the future. If the introduction of the minimum wage leads to reduced working hours—as evidence from previous literature suggests (Bossler and Gerner 2019)—individuals have more time to invest in their health. However, increased income raises the opportunity cost of time, making investments in nonmarket goods more expensive (Horn et al. 2017).

To analyze whether these pathways between minimum wage and health can explain the positive effect we find above, we again utilize information from our survey data. We use different proxies for each pathway (affordability, psychosocial effects, and worker and firm decision making) to put our results into perspective.

With respect to the affordability channel, we investigate whether the wages of treated workers indeed increased, a sufficient condition for a positive income effect. Subsequently, we test whether the introduction of the minimum wage is related to the frequency of sports activities, a common health-improving investment analyzed in the previous literature [see Horn et al. (2017), Lenhart (2017a)].

With respect to psychosocial effects, we use three different proxies. First, we use workers’ self-assessed job satisfaction. One important factor of worker job satisfaction may be wages. Hence, second, we use information on workers’ self-assessed satisfaction with their pay. Third, we analyze the relation between the minimum wage reform and the time pressure experienced by workers at their workplace, a factor that may determine their stress levels.

To analyze the third channel, worker and firm decision making, we use the number of working hours as a measure of time costs.Footnote 23

We begin with a descriptive comparison of the outcome variables before and after the minimum wage reform for treated and untreated individuals. Table 8 shows that the relative change in hourly wages was considerably higher in the treated group. On average, the hourly wage in the treated group increased by 27%, while it only increased by 15.5% in the control group. The average weekly working hours in the treated group decreased considerably—by 5.3%—while they did only marginally change in the control group.Footnote 24In sum, both developments result in an average increase in the monthly gross wage of 23% in the treated group and only 12% in the control group.

The frequency of exercising increased slightly more in the treatment group (8.4%) than in the control group (7.6%). Individuals in both groups answered that they were happier with their employment after the minimum wage reform. The increase was larger in the treatment group. Individuals in the treatment group reported that the time pressure they experienced at work had decreased (by approximately 2.6%), while it remained more or less the same for people in the control group. Furthermore, individuals in the treatment group answered that they were more satisfied with their pay (an increase of 7.8%), while individuals in the control group were equally satisfied before and after the reform.

To go beyond this descriptive analysis, we again rely on our regression approach using adjusted difference-in-differences models combined with matching.Footnote 25 Table 9 shows the results for the effects of the minimum wage reform on hourly and monthly wages as well as on working hours.

The minimum wage reform increased the hourly wages of treated workers on average by approximately 5–9%.Footnote 26 Next, we estimate the effects on (actual) working hours. The regression results suggest a decrease in (actual) weekly working hours by 1.74–2.68 h for treated individuals. In total, these results are manifested in an increase in monthly gross wages of approximately 5–7%.Footnote 27

These results—the positive effect on wages and the negative effect on working hours—indicate that the introduction of the minimum wage was actually binding and point to a positive income effect, which is a sufficient condition for the health-improving factors in the Grossman model. The reduction in weekly working hours might be interpreted as a time cost effect, at least potentially giving individuals more time to spend on health-improving activities.

To check how individuals spend their time, we utilized a survey question on the frequency of exercise. Figure 5 shows the effects of the minimum wage reform on workers’ exercise frequency. We estimate a random-effects ordered logit because the answers are on an ordered scale from “never” to “every day”.Footnote 28 Interestingly, we do not find any significant effects. Treated individuals do not seem to exercise more than individuals in the control group. This finding is consistent with the results reported in Horn et al. (2017) for men, but in contrast to Lenhart (2017a) who find the minimum wage introduction in the UK led to an increased likelihood of reporting membership in “sports clubs”.

To check the second channel, potential psychosocial effects, we use a survey question about worker job satisfaction. Workers are asked whether they are satisfied with their current job. The variable can take on eleven different values from totally unhappy to totally happy. Figure 6 shows the estimated marginal effects.Footnote 29 We find a positive relationship between the minimum wage reform and job satisfaction. Specifically, we find that affected individuals are less likely to report that they are unhappy (lower values) and more likely to report that they are happy (three highest values) with their job.

Next, we test the role of pay satisfaction. Workers are asked whether they are satisfied with their current pay. The outcome variable varies from “do not agree at all” to “fully agree.” Figure 7 shows the estimated marginal effects.Footnote 30 We find that the reform seems to decrease the probability of being dissatisfied by up to 4 percentage points but to increase the probability of being satisfied with pay by up to approximately 3.5 percentage points.Footnote 31 The positive effects on pay and job satisfaction are in line with Bossler and Broszeit (2017) who also study worker satisfaction in light of the minimum wage introduction in Germany but use a different data source.

Finally, we investigate affected workers’ stress levels at the workplace. Specifically, the survey asks whether individuals feel time pressure at their workplace. The outcome varies from “do not agree at all” to “fully agree.” Figure 8 shows that there is a negative relation.Footnote 32

Individuals in the treatment group have a higher probability of reporting that they do not experience time pressure but a lower probability of reporting that they feel time pressure (“fully agree”). We interpret this finding as a potential pathway for our health-improving effect which operates through reduced stress levels.

9 Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate the effect of a large minimum wage reform in Germany on self-rated health. Studying health effects is of particular interest for economists and policy makers because labor market reforms can have consequences that go beyond labor market outcomes.

Our estimation procedure uses exogenous variation in hourly wages induced by the introduction of the German minimum wage on the first of January 2015. This natural policy experiment enables us to conduct a difference-in-differences analysis combined with propensity score matching. We compare self-rated health changes among individuals who are most likely affected by the minimum wage reform, as their hourly wage prior to the reform was below the hourly minimum wage of €8.5, with individuals who were likely not affected by the reform. We use survey data combined with administrative records, which enables us to control for a vast set of possibly confounding variables.

Our results suggest that the minimum wage introduction led to a significant improvement in the self-rated health of affected individuals, which is in line with several previous studies [e.g., Lenhart (2017a), Andreyeva and Ukert (2018), Du and Leigh (2017)]. Quantitatively, increasing hourly wages increased the probability of rating one’s health as good or very good on average by 4 to 7 percentage points. Several robustness checks concerning measurement error, spillover effects and placebo tests support this result.

We analyze several pathways from the previous literature. On the one hand, we find that affected individuals earn higher wages but work fewer hours. On the other hand, affected individuals report that they are more satisfied with their job, including their pay, and feel less time pressure at work.

Policy makers have not considerably included health outcomes to the public debate. However, by law, the minimum wage aims at providing a “minimum protection” to all employees. In this vein, our results imply that policy makers should consider both the economic and possible health effects when altering the minimum wage. An interesting avenue for future research is to exploit heterogeneous effects for subgroups of individuals.

Notes

See, e.g., Neumark et al. (2007) for a review of the literature.

For studies that evaluate the labor market-related effects of the German minimum wage reform, see, for example, Bossler and Gerner (2019), Bonin et al. (2018), and Bossler et al. (2020). Only a few authors have analyzed nonmarket outcomes such as job or life satisfaction (Bossler and Broszeit 2017; Pusch and Rehm 2017; Gülal and Ayaita 2018).

See Antoni et al. (2017) for details.

Self-reported health may be a proxy for true health measured with classical error. In this case, the coefficients presented below would note change and the standard errors would be larger than if we had the true measure of health.

Alternatively, one could limit the treated and control groups to those individuals who actually receive or do not receive the treatment. We refrain from doing so to avoid the selection bias that might occur “if those who remain below the minimum wage are more susceptible to worsening health” (Reeves et al. 2017[p. 20].)

The choice of the bandwidth creates a trade-off between bias and variance. Hence, we attempt to minimize the mean standardized bias while keeping the standard deviation at a reasonable magnitude. Our strategy results in a bandwidth of 0.09. Our point estimates are robust to a range of bandwidths. These results are available upon request.

We are aware of the lively discussion about how to deal with uncertainty in models with propensity score matching [see Stuart (2010) among others]. We follow Ho et al. (2007) and do not take this uncertainty into account in the variance estimations. Evidence suggests that the standard errors obtained by doing so are too large and thus lead to more conservative inference.

The PASS consists of two subsamples: one subsample represents households in which at least one person receives unemployment benefits. The other subsample includes the general population of Germany, in which households with low socioeconomic status are oversampled (Trappmann et al. 2013).

The employer information stems from the “Betriebs-Historik Panel” [see Schmucker et al. (2016)].

In 2014, 11,590 individuals were interviewed in the personal questionnaire of the PASS. Since not all individuals have a record in the administrative data at the time of the survey interview (such as civil servants, the self-employed, etc. ), the number of individuals is reduced to 7,567. This includes individuals who refused linkage or were not registered as unemployed or employed on the date of the interview. We use parts of Eberle and Schmucker (2017) to properly link the survey data to the administrative records.

See "Gesetz zur Regelung eines allgemeinen Mindestlohns (Mindestlohngesetz - MiLoG (2014, August 11))".

These include workers in the meat industry; hairdressers; workers in agriculture, forestry and horticulture; temporary workers; workers in the textile industry or laundry services; newspaper deliverers; and harvest helpers (Gesetzliche Neuregelungen – Das ã 2014D).

There are 12 observation which are out of the common support. The reduction in the number of individuals is hence mainly due to the nature of our unbalanced panel, as past self-rated health enters our regression as an extra individual variable.

Monthly working hours equal weekly working hours multiplied by the average number of weeks in a month (\(\nicefrac {52}{12}\)).

Ahlfeldt et al. (2018) find that poorer regions—in particular regions in former East Germany—are more affected by the minimum wage.

The standardized bias in percentages \(\left[ \frac{100(\overline{x_t} - \overline{x_c})}{\sqrt{0.5(Var(x_t) + Var(x_c))}}\right] \) represents the mean difference between the treated and control group for each covariate (\(\overline{x_t} - \overline{x_c}\)) as a percentage of the square root of the average of the sample variance (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1985).

See Bossler and Westermeier (2020) for an evaluation of measurement error in minimum wages using survey data.

Figure 4 shows the coefficients from the regressions without matching. The coefficients from the regressions with matching are in the same order of magnitude and at least significant at the 10% level.

The standardized bias before matching for the dummy variables indicating the 16 federal states is 40.95. After matching, it shrinks to 5.78.

Evidence for the wage-"sin goods" relation for Germany is sparse. Using German survey data, Baktash et al. (2021) show that the likelihood of consuming alcohol is higher for workers receiving performance pay.

In this vein, Lenhart (2020) uses information on individuals’ health insurance in the USA and finds that a higher minimum wage increases their coverage. In Germany, however, statutory health insurance is compulsory, so usually all persons in dependent employment, affected or unaffected by the minimum wage reform, have the same kind of health insurance.

We do not restrict observations on the basis of their type of work. It may be the case that composition effects play an important role in the decrease in hours.

An interesting avenue for future research is to allow for treatment effect heterogeneity. Lehrer et al. (2021) provide a bootstrap-based multiple testing procedure for quantile treatment effect heterogeneity under the assumption of selection on observables.

Our wage measure includes all types of bonus and overtime payments. These results also hold qualitatively if we use contractual working hours instead. Results are available upon request.

We do not include the unemployed in the regressions presented in Table 9. To assess the effect on working hours for the unemployed, we additionally run regressions where we impose that individuals who became unemployed after the reform work zero hours in the post-reform years. The treatment effects are a reduction in weekly working hours of three to four hours.

The figure shows the results without matching. The regression results with matching are very similar. These are available upon request.

The figure shows the results without matching. The regression results with matching are very similar. These are available upon request.

The figure shows the results without matching. The regression results with matching are very similar. These are available upon request.

Figure B.1 in the “Online Appendix” shows that the same conclusion is true for workers’ satisfaction with their economic status.

The figure shows the results without matching. The regression results with matching are very similar. These are available upon request.

References

Adams S, Blackburn ML, Cotti CD (2012) Minimum wages and alcohol-related traffic fatalities among teens. Rev Econ Stat 94(3):828–840

Ahlfeldt GM, Roth D, Seidel T (2018) The regional effects of germanys national minimum wage. Econ Lett 172:127–130

Andreyeva E, Ukert B (2018) The impact of the minimum wage on health. Int J Health Econ Manage 18(4):337–375

Antoni M, Dummert S, Trenkle S (2017) PASS-Befragungsdaten verknüpft mit administrativen Daten des IAB (PASS-ADIAB) 1975–2015. FDZ-Datenreport, 6/2017, Nuremberg

Antoni M, Ganzer A, vom Berge P et al (2016) Sample of integrated labour market biographies (SIAB) 1975–2014. FDZ-Datenreport, 4/2016, Nuremberg

Arulampalam W, Booth AL, Bryan ML (2004) Training and the new minimum wage. Econ J 114(494):C87–C94

Autor D (2003) Outsourcing at will: The contribution of unjust dismissal doctrine to the growth of employment outsourcing. J Law Econ 21(1):1–42

Averett SL, Smith JK, Wang Y (2017) The effects of minimum wages on the health of working teenagers. Appl Econ Lett 24(16):1127–1130

Bacak V, Olafsdottir S (2017) Gender and validity of self-rated health in nineteen european countries. Scand J Publ Health 45(6):647–653

Backé E-M, Seidler A, Latza U, Rossnagel K, Schumann B (2012) The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85:67–79

Baktash MB, Heywood JS, Jirjahn U (2021) Performance pay and alcohol use in Germany. Discussion papers series no. 14205, IZA

Bellmann L, Bossler M, Gerner H-D, Hübler O (2015) IAB-betriebspanel: reichweite des Mindestlohns in deutschen Betrieben. IAB-Kurzbericht 6/2015

Bonin H, Isphording IE, Krause-Pilatus A, Lichter A, Pestel N, Rinne U et al (2018) Auswirkungen des gesetzlichen Mindestlohns auf Beschäftigung, Arbeitszeit und Arbeitslosigkeit, IZA Research Report No. 83

Bossler M, Broszeit S (2017) Do minimum wages increase job satisfaction? Micro-data evidence from the new german minimum wage. Labour 31(4):480–493

Bossler, M, Gerner H-D (2019) Employment effects of the new german minimum wage: evidence from establishment-level microdata. ILR Review

Bossler M, Gürtzgen N, Lochner B, Betzl U, Feist L (2020) The german minimum wage: effects on productivity, profitability, and investments. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 240(2–3):321–350

Bossler M, Westermeier C (2020) Measurement error in minimum wage evaluations using survey data. IAB-Discussion Paper 11/2020, Nürnberg

Bundesregierung (2014) Gesetzliche Neuregelungen – Das ãndert sich mit dem Jahreswechsel (2014, December 22) 2018, September 7 from https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Artikel/ArtikelNeuregelungen/2015/2014-12-22-neuregelungen-januar.html

Chaloupka FJ, Warner KE (2000) Chapter 29 the economics of smoking. volume 1 of Handbook of Health Economics, pp 1539–1627. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Clark KL, Pohl RV, Thomas RC (2020) Minimum wages and healthy diet. Contemp Econ Policy 38(3):546–560

Du J, Leigh JP (2017) Effects of minimum wages on absence from work due to illness. BE J Econ Anal Policy 18(1):1–23

Eberle J, Schmucker A et al (2017) Creating cross-sectional data and biographical variables with the sample of integrated labour market biographies 1975–2014: programming examples for stata. FDZ-Methodenreport, 06/2017, Nuremberg

Eriksson I, Undén A-L, Elofsson S (2001) Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. Int J Epidemiol 30(2):326–333

Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL (2005) The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. 62(2):105–112

Garbarski D (2016) Research in and prospects for the measurement of health using self-rated health. Public Opin Q 80(4):977–997

Grossman M (1972) On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Polit Econ 80(2):223–255

Gülal F, Ayaita A (2018) The impact of minimum wages on well-being: evidence from a quasi-experiment in Germany. SOEPpapers Multidiscip Panel Data Res No. 969

Hafner L (2019) Do minimum wages improve self-rated health? Evidence from a natural experiment. FAU discussion papers in economics 02/2019

Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Todd PE (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev Econ Stud 64(4):605–654

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA (2007) Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal 15(3):199–236

Horn BP, Maclean JC, Strain MR (2017) Do minimum wage increases influence worker health? Econ Inq 55(4):1986–2007

Kaufman JA, Salas-Hernández LK, Komro KA, Livingston MD (2020) Effects of increased minimum wages by unemployment rate on suicide in the USA. J Epidemiol Commun Health 74(3):219–224

Kronenberg C, Jacobs R, Zucchelli E (2017) The impact of the UK national minimum wage on mental health. SSM-Popul Health 3:749–755

Lechner M, Rodriguez-Planas N, Kranz DF (2016) Difference-in-difference estimation by fe and ols when there is panel non-response. J Appl Stat 43(11):2044–2052

Lehrer SF, Pohl RV, Song, K (2021) Multiple testing and the distributional effects of accountability incentives in education*. J Bus Econ Stat, online first

Lenhart O (2017) Do higher minimum wages benefit health? Evidence from the UK. J Policy Anal Manage 36(4):828–852

Lenhart O (2017) The impact of minimum wages on population health: evidence from 24 OECD countries. Eur J Health Econ 18(8):1031–1039

Lenhart O (2020) Pathways between minimum wages and health: the roles of health insurance, health care access and health care utilization. East Econ J 46(3):438–459

Marcus J (2014) Does job loss make you smoke and gain weight? Economica 81(324):626–648

Mindestlohnkommission (2016) Erster Bericht zu den Auswirkungen des gesetzlichen Mindestlohns. Bericht der Mindestlohnkommission an die Bundesregierung nach S9 Abs. 4 Mindestlohngesetz, Berlin

Neumark D, Wascher WL et al (2007) Minimum wages and employment. Found Trends Microecon 3(1–2):1–182

Paul Leigh J, Leigh WA, Du J (2019) Minimum wages and public health: a literature review. Prev Med 118:122–134

Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG (2015) Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med 128:316–326

Pusch T, Rehm M (2017) Mindestlohn. Arbeitsqualität und Arbeitszufriedenheit. WSI-Mitteilungen 70(7):491–498

Reeves A, McKee M, Mackenbach J, Whitehead M, Stuckler D (2017) Introduction of a national minimum wage reduced depressive symptoms in low-wage workers: a quasi-natural experiment in the UK. Health Econ 26(5):639–655

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1985) Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 39(1):33–38

Sabia J, Pitts MM, Argys L (2014) Do minimum wages really increase youth drinking and drunk driving? FRB Atlanta Working Paper

Schmucker A, Seth S, Ludsteck J, Eberle J, Ganzer A et al (2016) Establishment history panel 1975–2014. FDZ-Datenreport, 3/2016, Nuremberg

Stewart MB (2004) The impact of the introduction of the UK minimum wage on the employment probabilities of low-wage workers. J Eur Econ Assoc 2(1):67–97

Stuart EA (2010) Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci 25:1–21

Trappmann M, Beste J, Bethmann A, Müller G (2013) The PASS panel survey after six waves, die PASS-Panelbefragung nach sechs Wellen. J Labour Market Res 46(4):275–281

Trappmann M, Gundert S, Wenzig C, Gebhardt D (2010) PASS-A household panel survey for research on unemployment and poverty. Schmollers Jahr 130(4):609–622

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Hafner declares that he has no conflict of interest. Lochner declares that he has no conflict of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful for helpful comments and suggestions by Daniel Bias, Mario Bossler, Christian Merkl, Harald Tauchmann, anonymous referees, and participants at several seminar presentations. All errors are our own. An earlier version of this paper circulated as Hafner (2019)

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hafner, L., Lochner, B. Do minimum wages improve self-rated health? Evidence from a natural experiment. Empir Econ 62, 2989–3014 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02114-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02114-3